Winds of Change? The Role of Women Activists in Lahore Before and After Partition

SARAH ANSARI

This article addresses the role of women activists in Lahore during the years that straddled independence. While it considers earlier developments in pre-partition Lahore, its main focus is the important All-Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA) conference that was held there in 1952. Lahore, where women had taken part in Muslim League activities prior to August 1947, now hosted an international gathering attended by participants from all parts of Pakistan, as well as from abroad. The range of issues under discussion, together with the resolutions that were passed and the newspaper comment that was generated, provides historians with a way of identifying and assessing the concern of women more generally within the new state of Pakistan at this important early stage in its nations-building activities. This article show how this was so, by placing the conference against the backdrop of other debates relating the status of women that were taking place in Pakistan during the 1950s.

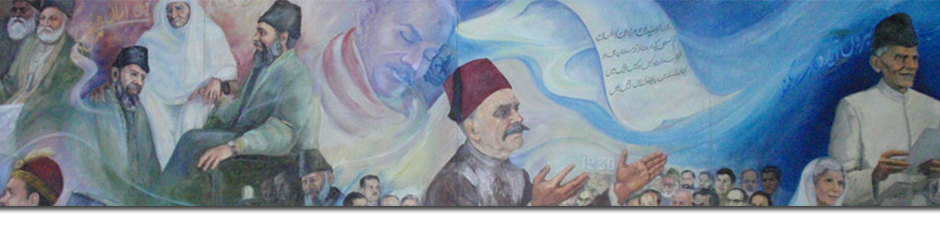

Lahore, capital of colonial Punjab, had proved itself to be a key location – or site – in terms of the participation of Muslim women in various spheres of ‘public’ life in the years leading up to independence and partition. Indeed, its proud tradition of providing women with access to education was testament to this reputation. The city had long been a centre of learning and intellectual debate in northern India, and this had extended relatively early on to women as well, thanks in large part (at least initially) to the efforts of the Anjuman-i-Himayat-i-Islam (Association for the Services of Islam) that had been launched in Lahore in 1884. Undoubtedly, one of the Anjuman’s major achievements was the establishment of a number of schools for Muslim girls and orphanages in different parts of the Punjab, where girls were taught Urdu and the Qur’an, as well as mathematics, needlework and other crafts. In 1885, it set up five girls’ school in the old part of Lahore, a number that had increased to 15 by 1894, though it then apparently declined to 8 in the early 1900s. Enrolment (though always limited) continued to fluctuate but ‘averaged from thirty to fifty students per school’.The Anjuman also set up a publishing house for ‘appropriate’ textbooks for Muslim girls’ schools, and these were used all over the Punjab and beyond. The outcome of all this effort was that Muslim girls’ education was relatively more advanced in Lahore in the 1880s and 1890s than in Delhi or Aligarh at this time, though of course many ‘respectable’ Muslim girls continued to be educated at home by other family members or tutors.

By the time of First World War, a number of girls’ Purdah Schools had been founded in Lahore, such as the Victoria Girls’ High School in the old city (at Bhati Gate), and the Queen Mary Girls’ High School that taught English and, as Minault has pointed out, was intended as female counterpart to Aitchson Chiefs’ College.Hence, in the mid-1920s, the Anjuman also took up the issue of secondary or collegiate education for women, and some of its schools, including the Anglo-Vernacular Islamia Girls’ Middle School founded in 1925, began to teach up to middle standard level. Later, in 1936, one of its establishments became a high school. Meanwhile, the Anjuman was making plans to start a women’s college, to complement its existing Islamia College that had been granting degrees to men since 1900, with the result that Islamia College for Women in Lahore was founded in 1939, whose curriculum was the standard Bachelor of Arts supplemented by an Islamic education.

Other well-known higher educational institutions for women that were established in Lahore during the early years of the twentieth century include Kinnaird College for women, the first women’s college to be established in the Punjab, which grew out of a Chirstians girls’ school founded in the 1880s and acquired its college status in 1913.Likewise, Queen Mary’s College, which grew out of the Queen Mary Girls’ High School (certainly operating by 1912), attracted students from elite families in a cross-section of religious communities. A third Lahore institution, also attended by girls from all communities, was the Lahore College for Women was established in 1922 in a small building in Hall Road to meet the needs of female students irrespective of religious affiliations. In 1951 it shifted to Jail Road (to what had been Sir Ganga Ram High School and Teachers Training Centre). Another, short-lived, attempt at setting up a girls’ college was the Muslim Girls’ College at Mozang (also referred to as the Fatima Girls’ School, and also Jinnah College), founded by Fatima Begum (former Superintendent of Municipal Urdu Girls’ Schools in Bombay, editor of both the women’s fortnightly Sharif Bibi and later her own weekly publications Khatun, and last but not least, sometime president of the Muslim League’s Women’s Committee).Fatima Begum had the vision of promoting vernacular higher education, and special arrangements were made for purdah and religious education. However this particular college, its seems, only survived for a couple of years thanks to the fact that female students generally preferred to attend institutions that offered government-recognised degrees. Minault later refers to Fatima Begum to as the Principal of the Islamia College for Girls, a role that she had apparently earlier declined when this Anjuman-i-Hamayat-i-Islam Institution was first being mooted prior to the Second World War.

Lahore’s role as a centre of Muslim women’s education, thus, directly helped to create a pool of potential support for the League by the 1940s. Many of the women who participated with vigour in the pro-Pakistan agitation of the mid-1940s had (to some extent or other) shared common educational experiences which shaped their political responses. As both Dushka Saiyidand David Willmerhave highlighted, the enthusiastic support of Muslim women in the city (and the Punjab more widely) for the idea of ‘Pakistan’ was linking to a history of local political activism that, as Saiyid has shown, dated back to the time of the Khilafat movement, if not earlier.It is perhaps no coincidence, therefore, that key speeches, in which League leaders such as Jinnah addressed the need for Muslim women to identify with the demand for Pakistan, were delivered in Lahore during this sensitive period. For instance, it was at the 27th session of the All-India Muslim league held in the Lahore in March 1940 (at which the famous Pakistan resolution was passed) that Jinnah made his famous comment that if political consciousness is awakened amongst our women, remember, your children will not have much to worry about.

Jinnah deployed a similar rhetoric when he addressed a meeting of the Punjab Girl Students Federation that, according to Saiyid, was held at the Jinnah Islamia College in 1942.

I am glad to see that not only Muslim men but Muslim women and children also have understood the Pakistan scheme If Muslim women support their men, as they did in the day of the Prophet of Islam, we should soon realise our goal.

Likewise, it was at a women’s fair, or mina bazaar, held at the end of 1945 in Lahore to honour Jinnah’s birthday, that Begum Jahanara Shahnawaz insisted that “Muslim women are fully alive to their responsibilities today and are more impatient for Pakistan than men’.When women took to the street of the city in sizeable numbers to take part in pro-Muslim League demonstrations over the winter of 1946-47, this was heralded as ‘the first such mass public mobilisation of women anywhere in pre-independence India’.

Undoubtedly, those women who supported Jinnah’s call to become involved call must have done so for a range of reasons, Some, not surprisingly, would simply have followed the example set by men folk in their families. But others reacted more independently, with their activism a reflection of the degree of autonomy that was permitted by unsettled political circumstances of the time. Either way, it would be hard to imagine that such women interpreted ‘Pakistan’ – whatever this was going to mean in practice – as a place where their rights, as females, would not be safeguarded. After all, had not their leader Jinnah himself been prominent in the campaign to secure the passage of the Shariat Application Act of 1937, which targeted the customary laws depriving women of their inheritance rights with respect to immovable property, and had particular resonance in somewhere such as the Punjab where customary law in relation to agricultural land prevailed. Similarly, the Muslim Dissolution of Marriage Act of 1939 had further reinforced awareness of the possibility of challenging existing interpretations of religious law in order to improve the relative position of women vis-à-vis that a men.

On the grounds of the ‘precedents’ such as these, it was not perhaps surprising that a growing number should become convinced that Jinnah’s vision of Pakistan’ offered Muslim women a better, brighter future, as far as their rights as enshrined in Islamic law were concerned. Indeed, these kind of perceptions help to explain why support for the movement for Pakistan spread as enthusiastically as it did to girls’ schools and colleges, at least in urban parts of the Punjab. As illustrated by Saiyid’s example of Azra Khanum, a student at the Lahore College for Women who called upon Muslim men to educate Muslim women in a speech delivered at the Town Hall in November 1942, women supporters of the League were adamant that they should participate in the Pakistan movement as the equal partners of men.Political liberation and the liberation of women, for them, were intimately, and inextricably, inter-twined.

Once Pakistan had begun to emerge, albeit somewhat gingerly, from the general confusion of partition, it entered a period of intense nation-building debate as to its identity, and what shape its institutions – constitutional, legal, political – should take. The Objectives Resolution passed by the Constituent Assembly in March 1949, which laid down that principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance and social justice (as enunciated by Islam) would provide the basis for Pakistan’s future constitution, set in motion intense debate about the role of religion in the functioning of both state and society, and in the process, this raised questions in relation to what role women, as citizens, were to play. In other worlds, earlier expectations aside, what was Pakistan going to be like in reality for its womenfolk?

As a result, with the constitutional framework still undecided, the late 1940s and early 1950s witnessed intensive lobbying by those who sought to protect women’s rights and to encourage the state to intervene ‘proactively’ on their behalf. This was a time when it was felt that nothing could be left to chance. Women activists , who more often than not (but not always) tended to belong to privileged backgrounds, used their various connections to ensure that issues concerning women’s lives were not allowed to slip off the government’s agenda. Organisations such as APWA, which could claim a certain degree of moral legitimacy thanks to the social work activities that its members had carried out among needy refugees women and children, were also conscious of the importance of defending women’s rights as ‘equal citizens’ within the new state. This did not mean that APWA’s leaders were necessarily happy about straying into what was more explicit ‘political’ territory. However, while its rhetoric emphasised social concerns, the actions that, at least some of, its members under took suggests that they were prepared to cross such boundaries if and when the need arose.

Karachi was the headquarters of APWA. As Pakistan’s capital city, it housed both politicians and top bureaucrats, precisely those men whose wives, daughters and sisters were proving themselves to be stalwart supporters of the organisation. But, unlike Karachi, as illustrated above, Lahore possessed a proven history of female activism in the public sphere, something that represented an asset on particular – public – occasions. It was, therefore, only fitting that in 1952, when APWA held its most ambitious conference to date, it chose to host this event in Lahore, rather than in any other Pakistani city. From 29 to March to 2 April, APWA’s annual conference was combined with an international gathering, widely (and proudly) touted as the first coming-together of Muslim women of its kind in South Asia (if not so-called Muslim world more generally). The overseas visitors, on whom much attention was lavished, included 11 from Iraq, 10 from Iran, four from Turkey, two from Indonesia, one from Beirut and one from APWA’s UK branch.

The Conference, as befitted its high profile status, was opened by the then Governor General of Pakistan (APWA’s main patron), Ghulam Muhammad. In his speech, he freely admitted that today, our women, generally speaking, are backward. This is an unfortunate fact, which we must admit, and I believe that our sisters from other Muslim countries will agree that the same conditions prevails in their countries too. Such a state of affairs is both un-Islamic and hindrance to progress. It is imperative, not merely for their own benefit but for the good of the whole nation, that our women should rise to their full stature and be active partners of men in the great work of national reconstruction. Pakistan has given and will give all facilities to women politically, and I am glad that our sisters in the new country are lucky that they have been saved unnecessary struggle which our sisters in their countries had to undergo to get what was and should have been their political rights… the problems before women in Muslim countries have many similarities. They are passing through various phases of social, economic and cultural progress, yet all this variety presents underlying unity of aims and objectives… Common causes of common ills leads inevitably to common remedies. This I take to be the main reason and justification for having troubled our sisters from all these countries to come here… I see all through the Islamic countries a movement amongst women to march ahead towards removing their disabilities and taking advantage of every possibility of service to their people.

One other point that Ghulam Muhammad stressed was the need for APWA to broaden its base of support. He called on the organisations to reach out more to the villages and, in his words, the masses. In what might be considered in retrospect to have been an over optimistic assessment of the degree of social equality now existing in Pakistan, he claimed that the age of privileged classes is gone. No longer can a minority of people live in comfort and luxury and the rest of the population exist merely to serve them.

Democracy and human dignity, according to him, were coming back into their own.

Begum Liaquat Ali Khan, APWA’s founder and life president, issued a similar plea, including a call for ‘national bias with an international outlook’, adding that there was no longer any question of the importance of such gatherings, and the intelligent and personal interests and contacts they foster are one of the surest and most lasting methods of establishing peace and prosperity through international goodwill and understanding.

Foreign delegates to the conference also made stirring introductory speeches during the opening session. Madame Ragia Hamza, representing the Women’s Renaissance Movement in Egypt’s Bint Nil Union, for instance, was the first to greet her fellow delegates. In her view, it was high time that Muslim women met more often to exchange views on subjects of common interests and then took joint steps to raise the standard of the women of various Muslim countries. As she explained, the way is long and hard, but it is the way which will ultimately lead to the consolidation of women’s status in the Islamic community. It will enable women to contribute their share in cementing ties among Muslim countries and thus save the world from anxiety, disturbance and disorder.

Madam Esma Neyman, ex-member of the Turkish parliament, similarly poured thanks on APWA for its initiative that had allowed ‘the women of the East’ to meet each other ‘in the heart-to-heart simplicity of an intimate gathering’.

Much of the first day was taken up with a resume of APWA’s past activities. In addition to emphasising the breadth of its domestic achievements, this assessment drew attention to APWA’s international links. Since no country could prosper in isolation, APWA had welcomed every opportunity to contribute to the work of international organisation working for improvement of women’s and children’s lives. Hence, on the recommendation of the United Nations’ Economic and Social Council, APWA had been granted the status of a consultant body under the category ‘B’. It had also represented at the International Alliance of Women’s conference held at Amsterdam in 1949, meeting of the Human Rights Committee at Geneva, the Conference of the World Associations of Youth, and the United Nations’ conference of non-government organisations at Bali. Most recently, in January 1952, it had sent delegates to the general meeting of the Pan Pacific Women’s Association held in New Zealand. As Begum Malik concluded.

APWA believes in the establishment of spirit of international brotherhood and in the improvement of the standard of living of the people. It has been responsible [for] fostering among Pakistani women the growth in international consciousness and a keen awakeness of responsibility to promote peace.

Following the symbolic exchange of national flags, which then were used to decorate the University Hall and, hence, mark in visual terms the extent of the internationalism that was taking place, the conference chalked out its plan for the formation of discussion groups which were divided into four main heads: economic uplift, education, art and culture, and health and hygiene.

Over subsequent days, the conference got down to brass tacks. Symposia and group discussions were held (often presided over by the foreign guests), and, in all, thirty resolutions were eventually passed. These resolutions covered a wide field, but essentially related to the eradication of illiteracy, improvement of hygiene, health and nutrition in village areas, research on cottage industries and the promotion, in particular, of rural welfare work through agencies capable of taking the initiative and ensuring coordination.While generally-speaking the emphasis lay on the extent to which APWA had become the best instrument in the education of public opinion for the advancement of women in Pakistan’, blazing the trail for a free, progressive and more purposeful life for them as a whole, Begum Liaquat, in her closing address, warned delegates against the kind of false complacency generated by ‘catchwords and political jargon’, and by ‘resolutions so glibly put down on paper’.But, as an editorial in the national newspaper, Dawn, striking a cautionary note, put it.

What matters is not resolutions but the will to carry them out. If the will is there, it can find ways and means. We expect the women leaders of this country to realise the implications of their own resolutions and the responsibilities which they have assumed enthusiastically. They have willingly invited the gaze of the whole Muslim world on their activities. Hard solid work is required of them during the twelvemonth lying between this Conference and the next, so that, at the end of this period, their organisation can give a better account of itself than the rhapsody of self-congratulation indulged in from year to year.

The newspaper (usually very supportive of APWA’s leadership) went on to welcome the organization’s acknowledgement that extensive and intensive village work could no longer be postponed – after all, as its leaders recognised, APWA had been criticized precisely on account of its privileged, urban, biases. Any rural campaign, Dawn urged, had to be organized with understanding and in a missionary spirit. It was not going to be a ‘cushy job’, ‘beginning with garlands and ending in cheers’. Initiative and leadership had to come from women themselves, and the very best of them had to be prepared to settle down for considerable periods, if necessary, in unattractive village surroundings to enter into that bond of mutual sympathy with village women that could only grow out of personal association and to initiate them into better living by example rather than by precept: ‘nothing short of work done on a woman-to-woman basis can produce useful results’.

This note of caution sounded by Dawn at the conclusion of the Lahore conference suggests that, despite the nation-building rhetoric that clearly characterised such events – and, in particular, the emphasis on women fulfilling their responsibilities as wives and mother to both their individual families and the collective nation – the call to Pakistani women to widen their public horizons by this time was not limited simply to issues of social concern. What is interesting, therefore, is to locate this 1952 Lahore conference in the context of the debates that were taking place at around the same time on the meaning and purpose of citizenship, debates that were more overtly political than the welfare stance usually favoured by Begum Liaquat and her associates.

Certainly, it was widely accepted that women had particular duties to perform as citizens of the new state – often they were presented in terms of being a good wife and mother – but these, it was increasingly argued, ought not to be confined to the supposed natural sphere of womanhood but had to correspond with the responsibilities of their male counterparts. As the Governor-General himself has pointed out, women in Pakistan (at least in theory) enjoyed the vote. There was more or less consensus on this. Instead, therefore, what became increasingly important to female activists (as well as their male supporters) was to ensure that women were empowered to participate in Pakistani life on the same political terms as men. At a time when the Constituent Assembly had still not managed to produce Pakistan’s first constitution, activists were particular concerned about the paucity of women that if contained. In the early 1950s only a hardful of women could be found in the provincial legislative assemblies. In addition, there were only two female members of the Constituent Assembly. Begum Shaista Ikramullah and the afore-mentioned Begum Jahanara Shahnawaz. And when the first Constituent Assembly was dismissed (in October 1954) and eventually replaced by a second Assembly was dismissed (in October 1954) and eventually replaced by a second Assembly, it had no women represented there.

The mid-1950s are usually associated with the lobbying of the state by female activist to secure the reform of Muslim personal law, in particular those aspects which related to polygamy and divorce. However, what is less frequently acknowledged is that this period was also marked by animated discussion over the question of women’s political participation. Hence, female activists were particularly disappointed that there were now no women in the reconstituted Constituent Assembly, with the Muslim League’s Khawateen Sub-Committee strongly condemning “the women MLAs of the Punjab, who is in spite of assuring the Muslim League Parliamentary Board, did not vote for the official women candidate.Not surprisingly, discussion about the role of women in the second assembly, together with developments that were taking place in relation to the actual drafting of the constitution, stimulated further demands for any forthcoming arrangements to address their needs specifically. As a result, a meeting of the recently-established ‘Women’s Rights Committee’ that was held in Lahore in August 1955 called for 15% representation for women in provincial assemblies and 10% in the national parliament.

Lahore during this period, therefore, remained a leading centre of concerted activity. In late October 1955, a 12-member delegation representing the ‘Unite Front of Women for Freedom and Protection of the People’s Rights’, led by the veteran activists Fatima Begum, by now President of Binat-i-Islam, submitted a Manifesto and Charter of Women’s Rights’ to the government for inclusion in the country’s future constitution. This set of demands explicitly condemned those women who were personally connected with men in positions of power, implying that they took advantage of this in ways that privileged them unfairly.

By the beginning of 1956, however, the second Constituent Assembly, minus any direct female involvement, had finally completed the task of drafting Pakistan’s constitution. Once its contents became known, some women activists were again quick to criticise them. Ending discrimination on the grounds of sex, it seemed, had found no place in the constitution; nor had equal pay for equal work been mentioned anywhere. Accordingly, activists such as Begum Shahnawaz called for women and their representatives to protest against the proposed constitution’s shortcomings.The outcome was a gathering of female activists in Lahore in the last week of January, with representative of a wide range or organisation including the Muslim League’s Women’s Committee, APWA, Lahore Ladies Club, YWCA, Pakistan Federation for Women’s Right, Anjuman Muhajir Khawateen, Binat-i Islam, All-Pakistan Christian League, Awami League Women’s Committee, Business and Professional Women’s Club, women members of the Lahore Corporation, as well as the six female members of the West Pakistan Assembly.The content of their resolutions demonstrated just how worried they were about the direction in which constitutional development were moving. The draft constitution, they believed, did not do enough to protect the right of Pakistan’s female citizens.Protests continued once the new constitution had received its assent at the beginning of March. In particular, many were unhappy about the presence of reserved seats allocated to women. As the Pakistan Federation of Women’s Right explained at the time, it had not been arguing in favour of special privileges for women, but for measures to promote and safeguard their fundamental rights, and these, it seemed, had been ignored by those drafting the constitution. Such protection was only the quid pro quo for the many efforts and great sacrifices made by Pakistani women during the country’s difficult early nation-building years:

Our leaders have called upon us many times during the past Eight years to play our full part in the life of our nation. We in turn now call upon our leader to guarantee our rights.

As this article has suggested, important debates were taking place among activists belonging to various women’s organisations in the decade following independence. These debates addressed a matter of critical national concern – the question of how to guarantee equality of citizenship within the new state to women and men alike. However, what is interesting is just how often it was Lahore that provided the setting where such discussions occurred. Whether it was APWA’s widely-publicised international ‘jamboree’ of 1952, or the lobbying undertaken by more critical organisations on the question of the constitution later on in the 1950s, the fact remains that it was frequently Lahore that witnessed these deliberations first hand. In this respect, the developments that took place in the years following independence continued directly in the proud tradition of female activism that had been established in the city over the decades leading up to 1947. And, more than half a century later, with the question of Pakistani women’s equal citizenship still unresolved, women’s organisations in Lahore remain at the vanguard of efforts of secure a better, brighter, future for their sisters across the country as a whole.